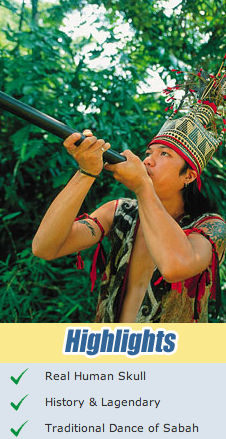

Anthropologists often criticize mainstream media for exoticizing people. But in Borneo you’ll find indigenous people who promote themselves as headhunters and are proud of it.

The journal Cultural Analysis has recently received a prize in the Savage Minds awards. It was voted as the second best Open Access anthropology journal. In the recent issue, folklorist Flory Ann Mansor Gingging writes about headhunting as an expression of indigenousness.

Headhunting is no longer practiced but the tradition has been commercialised by the tourist industry many places in South East Asia. But the headhunting past has not only taken on a commercial value, but also a cultural and political one, Flory Ann Mansor Gingging argues:

I propose that the tongue-in-cheek invocation of headhunting by the tourism industry represents one way in which Sabah’s indigenous people counter the outside world’s designation of them as the Other; that is, by parodying their headhunting past, they demonstrate their understanding of the joke and thus guard their indigenousness and their status as human beings.

(…)

Marginalized groups in Sabah, many of whom share a headhunting past, have re- written the headhunting narrative in their favor, becoming co-authors of a cause that seeks, in Hoskins’ words, “to seize an emblem of power, to terrify one’s opponents, and to transfer life from one group to another” (Hoskins 1996a, 38). Thus re-imagined, the headhunting narrative emerges as a tool useful in working towards change and equality.

(…)

Observed in cadence with past and present political milieus, the “refashioning” of the headhunting narrative within tourism in Sabah hence seems to reflect a general consensus among certain of Sabah’s native groups: that Otherness, strategically invoked and appropriated, provides them with an instrument for addressing external threats to their identities.

The anthropologist folklorist and doctoral student in the Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology at Indiana University grew up in the village she writes about. One of her friends, herself an indigenous Sabahan, said the headhunting imagery and narrative in tourism promotion is “embarrassing but cool":

“It’s beyond comprehension that I have ancestors that might have been headhunters. At the same time freakish ancestors totally distinguish you from the rest of the global population, so it’s secretly thrilling as well. I love seeing the slightly raised eyebrows reaction I get when I tell someone new I’m from Borneo.”

The researcher heard lots of stories about headhunters during her childhood. As she grew older, her relations to these stories changed:

As I got older, I began to be aware of the economic and political struggles that indigenous people in my state face. Since becoming part of Malaysia in 1963, Sabah, a former British colony, had never had a chief minister who was both indigenous and non-Muslim. Consequently, when in 1984, Joseph Pairin Kitingan, a Dusun lawyer, became the first non-Muslim native to assume this position, being indigenous suddenly meant something to me.

It was also around the same time that I remember feeling a new attraction to the macabre and exotic elements of my culture—one of them being headhunting. Without quite knowing it, I was invoking those aspects of my culture that were potentially embarrassing as a way of responding to the threat I felt towards my own Dusun-ness. For me, headhunting ceased being just a part of history and became, in the most personal way, a part of my heritage—an expression of my indigenousness.

In my opinion, making headhunting such a visible icon of tourism in Sabah is an example of what Michael Herzfeld calls “cultural intimacy,” which he describes as “the recognition of those aspects of a cultural identity that are considered as a source of external embarrassment but that nevertheless provide insiders with the assurance of common sociality” (Herzfeld 1997, 3).

A good example for this trend is the Monsopiad Cultural Village. Here, she writes, Herzfeld’s “cultural intimacy is performed". Although it is by no means the first to use the state’s headhunting histories within the context of tourism, she believes the Village is the only tourist site that has developed an entire park around the headhunting theme.

On the village’s website they write:

Monsopiad Cultural Village, the traditional village is a historical site in the heartland of the Kadazandusun people and it is the only cultural village in Sabah built to commemorates the life and time of the legendary Kadazan and head-hunter warrior: Monsopiad. The direct descendants of Monsopiad, his 6th and 7th generations have built the village on the very land where Monsopiad lived and roamed some three centuries ago to remember their forefather, and to give you an extraordinary insight into their ancient and rich culture.

Read the whole article:

>> Flory Ann Mansor Gingging: “I Lost My Head in Borneo": Tourism and the Refashioning of the Headhunting Narrative in Sabah, Malaysia

SEE ALSO:

Ainu in Japan: Cool to be indigenous

In Norwegian TV: Indian tribe paid to go naked to appear more primitive

“They still eat their fellow tribesmen”

Anthropology and tourism: Conference papers are online

Thanks for focusing attention on Flory Gingging’s fine essay. It is great that your post will bring it and _Cultural Analysis_ additional attention. Hopefully she will comment here herself. I would just note, for the good of the field that she and I share, that she is a doctoral student in the Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology here at Indiana University and that while that status hopefully qualifies her for membership in the global community of anthropologists, she is technically a folklorist. As someone who lives among both North American anthropologists and North American folklorists, I would note that research on heritage issues is particularly advanced among folklorists. The work of Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett’s (cf. “World Heritage and Cultural Economics"), Dorothy Noyes (cf. “The Judgment of Solomon” also in Cultural Analysis), and Valdimar Halsteim (cf. The (Politics of Origins") can be cited as illustration of this broader trend.

Thanks again for giving Flory’s paper such detailed attention.