By Aleksandra Bartoszko. Oslo University Hospital, Equality and Diversity Unit

See part I of the interview Being radical critical without being leftist and part II The global trade with poor people's kidneys

Nancy Scheper-Hughes is currently working on finishing her book, which will summarize more than ten years fieldwork on organ trafficking. In this interview she tells us about A World Cut in Two: Global Justice and the Traffic in Organs and she shares her reflections on challenges of doing and disseminating multi-sited research.

AB: What is your upcoming book about?

– It’s about trafficking - trafficking kidneys and other organs and tissues from people living on the edges of the global economy.

– There is also a chapter on the body of the terrorist, which is about cases of the medical abuse of enemy bodies harvested for usable tissues and organs at the Israeli forensic institute, as well as in Argentina during the dirty war and in South African police mortuaries during the anti-apartheid struggle when Black bodied piled up in the morgues.

– So I’m looking also at the harvesting of the dead body during periods of warfare and other conflict, a story that is a hidden subtext of modern warfare. Sometimes this is done as a kind of retaliation or retribution or as a punishment or as way to reinforce the fabric of individual bodies and the Body Politic.

– Since Margaret Lock did such a wonderful work on brain death, I also tell some stories about the very different ways that brain death is calibrated and understood from country to country. You can be brain dead in one country and not in the country next door. Or in US, you can be brain dead in one state, but not in another.

– So this is a very indeterminate form of death and this continues to contribute to people’s anxieties about donating organs. People sense this indeterminacy. How do you know he’s really dead? And the answer might be: “It depends on whether you are in Philadelphia or in New York City how dead you are”. And that is not very consoling answer.

AB: When can we expect your book?

– I am completing two books next year, one in January and the other in June. Right now I am working on a small monograph based on one of the chapters, which was too big for the organs trafficking book. It is about a war within the dirty war in Argentina, a war against the population of mentally and cognitively impaired at the war national asylum, Colonia Montes de Oca. It is called: “The Ghosts of Montes de Oca: Naked Life and the Medically Disappeared”.

AB: The working title of your trafficking book, “A World Cut in Two”, which refers to the countries of buyers and the countries of sellers, the rich and the poor, but also the world of the body, as you said. Speaking of body – if we move back to your article on three bodies you wrote with Margaret Lock in 1987. Has your view on the body in anthropology changed after your work with organ trafficking?

– Well, I always said that three was simply the magical number. People remember it. But I liked what Per Fugelli said – about the “missing body” in anthropological writings – the body in nature. And that would be not a naturalized, universalized body but the body as it is lived /interpreted in different times and places, as part of, and responding to, the given natural world. And I think that’s more important than all the promises inherent in genomics, biotechnologies and biosocialities.

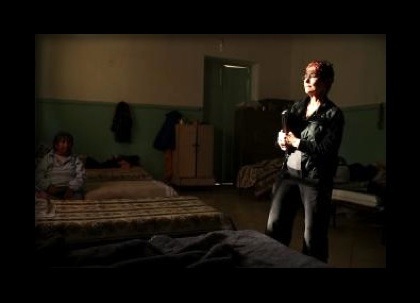

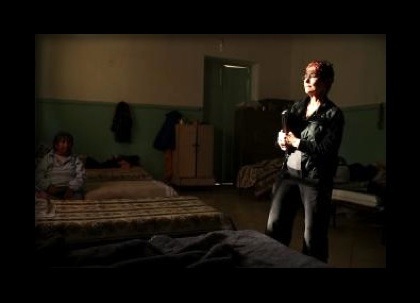

Nancy Scheper-Hughes. Photo: UC Berkeley

– Nonetheless there was a truly radical breakthrough on the particular day in Berkeley that Paul Rabinow had an a-ha! moment when he recognized following a particular class meeting on the AIDS epidemic as it was emerging in San Francisco that people in afflicted communities, who grappling with an epidemic that was not yet well understood, were forming social movements, alliances, identities, and affinity groups based on their T cell counts, that is on something that was invisible and unknown to them about human biology prior to the HIV/AIDS crisis. Thus, bio-sociality.

– So these other understandings of the body go beyond the ‘three bodies’ that Lock and I wrote about in ‘The Mindful Body’. Foucault anticipated it, of course. But I think that were I to revise the ‘Mindful Body’ today it would definitely include the body in nature, as both Per and Benedicte Ingstad have paved the way in their writings.

– And of course I would have to talk about biopolitics and biosociality and its effects. The advent of genomics, personalized medicine which also connote a different kind of body, a body that is potentially infinitely malleable. And in case of organs and organs transplant, which has been with us already quite a long time, the idea of the body is seemingly endlessly renewable.

– My colleague Lawrence Cohen refers to bodily “supplementarity”, this is the idea that I can supplement my body with your body parts and with all the bio-available materials I can get, legally or not, ethically or not, from the living or the dead.

– Bio-supplementarity is a more theorized version of what I called neo-cannibalism, to refer to the conditions under which I may have permission or assume the right to cannibalize you. While neo-cannibalism or compassionate cannibalism derives from a long anthropological tradition, it proved quite offensive to some readers, as you might imagine.

– And I suppose if I wanted to add a fifth body, it would probably be the body in debt. Because everywhere I go on behalf of the Organs Watch project I find that debt, debt peonage, debt to family, debt across generations is the cause of the redefinition of the duty to donate organs while still living, a phenomenon I have called the “terror and the tyranny of the gift”.

– The duty to survive and the duty to deliver organs has created a new and alarming form of embodied debt peonage. The debtors are the kidney sellers who, even as they dispose of their organs, no longer feel that they own them, there are claims being made on their bodies that they are unable to resist.

AB: Do you think these books will change anything or you feel that you’ve done enough and people who should know about the situation of the organ trade already have this knowledge?

– Well, I don’t know. What I really wanted to challenge and to change was the international transplant profession. I wanted them to acknowledge what was happening within their field, how it was being transformed by organs markets. And I think that that I have accomplished that.

– Indeed, I know I have gotten the profession to move beyond its initial denials – first that it was an urban legend that did not exist at all; then that it was the result of a few bad apples in the field; and third, and the most dangerous, the problem is small and we have corrected it.

– Now, since the Istanbul Summit on Organs Trafficking in 2008 (in which I, as director of Organs Watch, participated) the transplant world reached a consensus that accepted the reality of human trafficking in organs and the role that surgeons have played, knowingly or not, in its development. They acknowledged that trafficking in humans for organs is not like other forms of medical migration or medical tourism. It is unique.

– But as for the general public, so to speak, I think there are many people who still think this trafficking in organs is surreal, that is grist for horror movies not for scientific study. I have worked on several excellent documentaries on various dimensions of human trafficking in organs, but many people say: “I’m so surprised”.

AB: Who do you see as readers of your upcoming book?

– We used to say that we wanted to aim for a broadly educated public, “the readers of the New Yorker Magazine”. Easier said than done because we have dual obligations to write for anthropologists and social scientists, to develop social theory, and at the same time to educate and engage the public. To be a good citizen, to be a public intellectual. And these dual obligations often come into conflict.

– So, my book combines narratives within narratives, some aimed for the anthropologist and some for the public. It has plot, character development and is an anthropological detective story, you might call it a social thriller, perhaps. A new genre of ethnography. And why not?

– As in my previous ethnographies, Saints, Scholars and Schizophrenics and Death without Weeping, I want there to be food for thought for people who want to read ‘thick description’, thick interpretation, and others who will skip that and go for the action. I hope they will enjoy reading about some of the unforgettable characters that I have had the good fortune to meet along the organs trafficking trail.

– The hardest thing for me was that there were so many sites and so many countries I visited that the book was fragmented. Is there such a thing as a multi-sited over-load factor? If so, I have certainly suffered from it. And then, the world of transplant trafficking was always in flux, always moving to new sites, new organs, new arrangements. So I have written the book three times. I am now revising a fourth version. And some of it is still a bloody mess because I am jumping from Turkey to Israel or to the Philippines, to Europe.

– It’s like seeing the world through the animated kidney. Part of the book is also a reflection on the role of the anthropologist in studying organized crime and kidney pirates.

– A friend and former owner of a famous book store, Codys, in Berkeley, that (like so many other bookstores) collapsed under the pressure of Amazon.com suggested that I change the title of my book to “Kidney Hunter”. That is with reference both to the kidney traffickers and to the anthropologist who is another sort of kidney hunter. Or Notes of an Apprentice Anthropologist-Detective”. So I am playing with writing a sequel along those lines.

AB: But aren’t you afraid that when you are jumping from one place to another that we don’t get enough knowledge of each of these locations?

– You get to know enough about what you need to know to understand the meaning of transplant and the body in that particular location or country. I am not an ethnographer of Turkey or of Israel or Moldova, or of Argentina, or South Africa but I am an ethnographer of global organized crime, an ethnographer of global outlaw transplant. So perhaps it’s not traditional ethnography but it is anthropology, if you can accept that distinction.

– It is not a Malinowskian ethnography and has no pretence to be that. But it is using all the tools of anthropology and of ethnography, which is approaching people as having local worlds, local ethics, local morals, local bodies, and those are the ones that I have to understand, having at least minimal empathy for everyone involved which I always have.

AB: In many occasions you, as well as other anthropologists doing multi-sited fieldwork, have been accused of not being anthropologists for that anymore. How do you meet these comments?

– The problem for traditional ethnography is globalization, of course, which impacts all of our former research sites and populations. The people want to study are in movement, small communities are in flux, they are influenced more by what goes on outside their villages and slums and cities than what goes on inside them. So, we follow different objects.

– If I am following kidneys, others are following migrant labor, or looking at other forms of border crossing, at tourism, or financial markets, or humanitarian workers, or soldiers of fortune, all the ways that people are involved in maintaining lives at all levels of society.

– What’s happened to the practice of traditional ethnography is also the legacy of the savage attacks on the authority of the anthropologist and on the history of our discipline and its links to colonialism and, in USA, the relationships of some anthropologists with defense work and collaborations with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and so forth. We weren’t always on the right side of things.

– Beginning in the late 1960s we tried, my generation in particular, to “reinvent” anthropology, to address colonialism and imperialism and the Vietnam War as critics. Then, in the 1980s we began to turn those critics on ourselves as agents and to engage in brutal self-critical reflexive writings, deconstructing the objects and aims of anthropology.

Video: Already in 1998 George Marcus wrote a book about multi-sited research: “Ethnography through Thick and Thin”

– In the end we were deconstructing ourselves, as anthropologist, as Americans, as gendered persons, as social classes, to the point that we became so self-conscious of our personal, cultural baggage that many anthropologists simply gave up doing ethnography and became moral philosophers of a different sort.

– The idea that fieldworkers could, in fact, become friends, co-producers, co-workers, colleagues and even comrades, was thrown out as an affectation an artifice of the anthropologist. How could you really develop anything more than methodological empathy with the people you were studying? Younger scholars became uncomfortable with the idea of the anthropologist as both “stranger and friend”, as my mentor, Hortense Powdermaker put it. Where does the authority of the ethnographer come from, what gives one the right to infiltrate a community and to use intimacies to generate theories?

– Well, I still think that doing traditional fieldwork is essential, but I would say in the last few generations of our graduate students think that ethnography is an archaic approach. The world is no longer localized. There are always local communities but they are more influenced by what goes on outside of it than what’s going inside of it. So you have to engage these communities through what my colleague Laura Nader calls vertical slice, that is looking at power relations, at relation to the state, global relations.

– Today, in medical anthropology many graduate students now do science studies and they do so for variety of reasons. They believe that biotechnology is totally transforming bodies, psyches (the inner life), what is means to be human. Ethics, power, meaning – all of these seem linked to the possibilities of biotechnology. They also feel, following Paul Rabinow, that the only way to truly have a friendship with ones informants is to share knowledge experience and a social class relation.

– So the idea of studying up as Lauren Nader called it many years ago became the fashion. You studied Wall Street, insurance companies, bankruptcy courts, and global pharmaceutical companies, not the underdog, the exploited and the oppressed. But that was a misrepresentation of what Laura Nader was really saying. She said, study both. Don’t just study sugar cane cutters. Study the owner of the sugar plantations. Don’t just study the sweat shops workers in Asia. Study the American corporations that are using, buying and consuming their products.

– So as result of all these different forces, how you situate yourself, who you are, your class position, your historical background, it almost naturally emerged that people would do much more fragmented, partial and mobile approach to ethnography.

– So maybe the idea that we now engage in studying global assemblages and leave behind traditional ethnography is an over reaction. But it’s a real reflection of what the world looks like now. And, personally, I think it would be completely tragic to give up the Malinowskian approach altogether. I tell that to my students all the time. Some of the students of Benedicte Ingstad said: “What I learned from Benedicte was to write about what you know, and what you know well”.

– In that empirical, interpretive and Clifford Geertzian notion of thick description you cannot do thick description doing multi-sited anthropology. You can do thick theoretical analysis, you can do a lot of analytical work, but the thick description requires that you just dig in your heels, as we say, and stay. Stay as long as necessary. With many happy returns.

See part 1 of the interview Being radical critical without being leftist and part 2 The global trade with poor people's kidneys

It is a very interesting interview, and I would love to read about neo-cannibalism and brain death. But I think Scheper-Hughes’ focus on globalism is too much. It is hype. Just because everyone is talking about it, so do we. In reality though, there’s no such thing as globalism. It is irrational to believe there is. Remember that science is based on scepticism, and be more sceptic. Dont just believe what everyone else is saying, try to find out if it works. Pragmaticism.

Ofcourse, I am exaggerating here aswell. Just because something is a social construction does not make it less “real". But I am using the argument of reductio ad absurdum, to get a point across. Hope it worked