Can studying religious movements give us new insights into globalisation or even cosmopolitanism? Anthropologist Tulasi Srinivas thinks so.

Antropologi.info book reviewer Tereza Kuldova has taken a closer look at Srinivas’ new book Winged Faith: Rethinking Globalization and Religious Pluralism Through the Sathya Sai Movement.

—-

Book Review: Winged Faith: Rethinking Globalization and Religious Pluralism Through the Sathya Sai Movement by Tulasi Srinivas, New York: Columbia University Press, 2010

Tereza Kuldova, PhD Fellow. Museum of Cultural History, Department of Ethnography, University of Oslo

Tulasi Srinivas draws us with her book into the intriguing world of a transnational religious Sathya Sai movement, a movement that crosses regional, national, religious and cultural boundaries and thus creates something that she labels ‘engaged cosmopolitanism’.

Through the focus on this religious and cultural movement that has its roots in India and that has managed to grow into a huge global movement with millions of followers and devotees, she tries to resolve what ‘cultural globalization’ might mean in contemporary world. At the same time, she addresses the questions of the nature of transglobal economies of spirituality, affect and religio-cultural identity and the meanings and forms of new pluralism, as they can be exemplified through this movement.

Her detailed ethnographic study based on nine years of fieldwork, makes it clear that processes of globalization cannot be perceived in terms of westernization, as some would like to have it. They must be understood in terms of interactions, flows and movement between variously localized cultural centers and in terms of the resulting variously spatially and culturally localized translations of these interactions, images, ideas and discourses. To put it simply, flows are multidirectional (though I would say, this has never been different).

“Dynamic ethnography”

Tulasi Srinivas is throughout her work making an appealing argument for a ‘dynamic ethnography’, which operates with the concepts of mobile description and multi-sitedness. The problem she tries to resolve in her writing is how to comprehend mobility and how to deal with translocal phenomena and that within a discipline so ill equipped to understand them. Hers is a critical hermeneutic study of religious globalization, where concepts such as complexity, relationality, networks, interaction and affectivity play a crucial role.

Even though this type of logic is generally appealing and without any doubt trendy, there is still something that disturbs me in her work. It might be the constant concern with ‘cultural globalization’ and ‘cultural translation’, even after reading the book I still find myself wondering what exactly does that mean, where does one culture begin and the other end, what is borrowed, what authentic, what reinterpreted? Maybe we are just looking here for artificial isles of safety in a sea of constant flux… The question is - can we not do without these isles?

Hinduism-Muslim culture of saints, Christian teaching + indigenous healing rituals

Let me now provide you with a brief sketch of the book and then discuss one of the chapters in more detail.

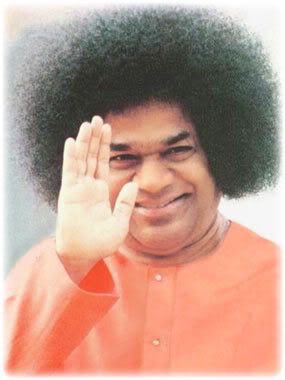

Throughout her book, Tulasi Srinivas introduces us to the story of the Sathya Sai movement. This movement is sixty-five years old and draws on a Hindu-Muslim culture of saints and mystics and on several strands of religion in the subcontinent, from Sufi mysticism, popular Hinduism, and Buddhism to indigenous healing rituals, Zoroastrianism and contemporary Christian teaching. The movement is centered on the charismatic personality of Shri Sathya Sai Baba (b. 1926).

Sai Baba was born in a remote village of Puttaparthi in Andhra Pradesh and “after suffering a series of seizures and falling into trances, he declared his greatness at the age of thirteen and proclaimed that he was Sai Baba, a reincarnation of Shirdi Sai Baba, a Muslim saint from Mahara who had died in 1918” (p. 9). He substantiated his claims by performing miraculous acts, such as materializations of sacred ash that devotees apply on their foreheads. These materializations continue to be central to his practice and are a matter of dispute among the members of anti-Sai movement.

Spiritual travel and “sexual healing”

Tulasi Srinivas maps the way this movement of his following has grown and became popular with people all around the world. She devotes a part of the book to the discussion of the nature of contemporary spiritual travel to the ashram in the village of Puttaparthi and the viewing and experience and magical encounter of darshan (witnessing of divinity) of Sai Baba. She takes us into the world of the global Sai community that stretches from the village of Puttaparthi to Tokyo, London, Hollywood, Mumbai, Bangalore and many other places around the globe and tries to grasp what it means to be and become a part of this global Sai community.

The chapter 4 is noteworthy because of its controversial nature. Tulasi Srinivas poses here the questions considering democracy, transparency and theology within the Sathya Sai Organization and focuses on the discussion of the allegations of ‘sexual healing’ and the ‘strategies of secrecy’ that according to her pervade this organization. In this respect, it is instrumental to read the reactions of the Sathya Sai Organization to her book, and in particularly to this chapter on http://www.saisathyasai.com/tulasi-srinivas/.

This controversy might be of interest to anyone possessing deeper knowledge of the movement and studying it, and it is up to the reader to make any conclusions. However, such critical comments are possibly the result of the fact that Srinivas dared to include the perceptions and views of the anti-Sai movement and did not only restrict her ethnography to the experiences of the committed devotees. On the other hand, how accurate any of the data is, is very hard to judge for anyone outside the movement and without its deep knowledge.

Further, she includes an interesting discussion on the encoded bodily prescriptions in the ashram and the problems they pose to the devotees from different cultures. She understands the failure of certain devotees to abide by the ashram rules as illuminating the “differential understanding of embodiment, salvation, desire and discipline” and believes that it speaks to “problems in cultural translation” (p. 19).

Branding of religious goods

However, the most intriguing chapter is according to me, being keenly interested in material culture, the last one dealing with the paradoxes of the teaching of resistance to the material world on one hand and the excessive consumption of religious objects on the other. In this context, “the material object is rejected as ‘unreal’ and a distraction from the truth of divinity, but the objects themselves become a significant signpost indicating the road to self-transformation” (p. 290).

Tulasi Srinivas shows us nicely how the consumption of these religious objects, be it gifted sacra or bought ephemera, has the power to directly transform the selves and the habitus of the devotees.

The gifted materializations (rings, necklaces, talismans, sacred ash, ambrosia etc.) from Sathya Sai Baba are the most important of the religious objects. “The reception of a materialized object instantly raises one’s standing among the community of devotees, as it is read as a sign of divine favor and an index of one’s active piety” (p. 285).

The materialized objects gifted by Sai Baba are believed to be transformed by the contact with him and thus possess a magical transformative power within them, “capable of transforming people’s bodies and minds from sick to well and from skeptical to devotional” (p. 294). “The gifting of the materialized objects to the faithful is the key element of transformative interaction between deity and devotee, as it is believed to be the material form of the much hoped for transference of the divinity’s grace and power as a blessing to the devotee” (p. 297).

Though gifts are the most important religious items for the Sai devotees, most of them never meet Sai Baba and are thus dependent on the global distributive network of Sai Baba goods, that can be purchased almost anywhere in the world. However, the further from the village of Puttaparthi, the less ‘authentic’ and powerful these objects get.

This chapter thus draws us also into the world of branding of religious goods, and the branding of the movement as such. What began as small business in touristic souvenirs in the 60s was turned into a bigger business in religious souvenirs in the early 70s mostly for spiritual tourists. By the beginning of 80s a huge business in religious objects of international scale, dealing in all kinds of objects, ranging from images, photographs, CDs, books, to jewelry, all featuring Sai Baba, was in place.

After all, the “Sathya Sai movement is known to be the largest faith-based foreign exchange earner for India, earning approximately Indian Rs. 881,8 million (approx. $5 million) for the year 2002-2003” (p. 12). Srinivas draws us also into the intricacies of the trade in the Sai Baba goods, where the SSSO claims to be the only ‘authentic’ source of ‘blessed’ goods by Sai Baba and where the struggle for perfection of the purchased goods is central.

Engaged cosmopolitanism or Hindu superiority?

To conclude, we can contrast the idea of ‘engaged cosmopolitanism’ which Srinivas uses with a statement of one of my informants, a lady who has been a spiritual tourist for the last 20 years and managed to escape her obsession: “After seeing all these babas and the way they treat people, you realize that most of what is happening is about power and money, the one who gives most gets those materialized gifts, the one who pays most gets to sit next to Sai Baba, in the end it is only a huge money-making industry and highly hierarchical one. And what is worse, the whole agenda of this money-making business is not a peaceful message of acceptance and equality of all religious beliefs, but rather the opposite, namely the superiority of Hindu thought and the Hindu dominance in a global sphere, after all India is shining. And magic, they can do no magic, why don’t they treat the lepers waiting outside their ashrams?” (Interview, 18. august 2010).

Engaged cosmopolitanism? Depends on what you imagine under this term.

This book on its all appears to be well-researched and is without doubt well-written, though at times it might seem too chaotic and the arguments unnecessarily literally twisted. A struggle for more clarity would be advisable. That does not diminish the contribution of the author to the studies in transnational religious phenomena. The book would be of interest to any scholar or student of globalization, religious movements, India, and to anyone interested in the methodological challenges posed by multi-sited fieldwork. And I would say, it is a must read for any Sathya Sai devotee!

Tereza Kuldova

—-

>> Information about the book by the publisher (Columbia University Press)

>> Review by Peter Berger (The American Interest, 3.8.2010)

>> Interview with Tulasi Srinivas (Lokvani 3.2.2006)

See more reviews by Tereza Kuldova, among others The deep footprints of colonial Bombay and Hindi Film Songs and the Barriers between Ethnomusicology and Anthropology or Colonialism, racism and visual anthropology in Japan: Photography, Anthropology and History and my look at her master’s thesis That’s why there is peace

Recent comments