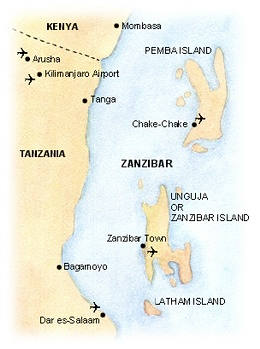

(Links updated 1.6.2021) How does everyday life change when electricity becomes available to people in a village in Zanzibar, East Africa, for the first time? Anthropologist Tanja Winther answers this question in her new book The Impact of Electricity. Development, Desires and Dilemmas.

The book is based on her doctoral dissertation and was also published in Swahili. “I think it would be a good thing if phd-budgets in general included the important step of making results accessible to the people under study”, she says in an email-interview with me.

“Electricity is a social phenomenon, and I hope that many anthropologists will join this fascinating field”, she adds.

Here is the interview:

So what has changed after the introduction of electricity?

What was most striking to me was the tremendous effect electricity has had on people’s time management. With electric light the day in theory has 24 hours instead of 12. People must make new choices as to what to do when. In consequence, time is speeding up and practices change: Women cook only two meals each day and not three as they used to (they now serve leftovers for the third meal). This is also linked to their wish to watch television in the evening and their opportunity to earn money during daytime.

Relations change in the process; the man has ‘entered the home’ in a new way. In the evenings, men and women now sit together in the same room, together with neighbours and the extended family. The electric light provide transparency and purity and the television programme is in focus. The paradox, although a phenomenon also observed in many other places, is that the spouses new opportunity to spend more time together actually provides less time for marital (?) intimacy. Sexual patterns change due to electricity. Because of this and also electricity’s high cost and rapid normalisation, there are signs that the birth rate is on the decrease. This was exemplified when men complained to me that due to the need for electricity, it is becoming too expensive to have more than one wife, or even get married at all.

People’s relationship to spirits also change; electric light is said to make space safer. Elderly, Swahili-speaking people would therefore refer to the new technology as ‘security light’.

Health wise, electrified water pumps and improvements in the health services (ex light at night time at the local clinic when a woman is in labour) has had a direct positive effect in development terms.

The arrival of water taps in the village implies that girls do not have to spend long hours fetching water from wells. Instead they are sent to school to the same extent as boys. Children, also girls, attend night classes before important exams and sleep in the school building. This surprised me, because parents in this Muslim context pay considerable attention to controlling girls’ whereabouts. I guess they have faith in the teachers looking properly after their children. But this also speaks of the tremendous importance people put on education in rural Zanzibar these days.

What are your thoughts about these changes?

When I started this study I was determined not to expect that electricity would bring ‘development’ to the countryside in Zanzibar. Overall, however, I am convinced that people’s new access to electricity has been a change to the better. Electricity is so fundamental when it comes to people’s access to information, to public services and to making the hard life in this region less physically demanding.

The notion of development in Swahili (maendeleo) is all about getting new ideas and new things that make you move forward. Following a grounded, entitlement-based approach to development one may even conclude that it should be a human right to have access to electricity. What they use electricity for must of course be left to the people in question to decide.

There are also problems, however, one challenge in Zanzibar being linked to the unequal structures that were also at work before electricity was introduced. In particular, I would highlight women’s lack of rights to inheritance and the fact that the divorce rate is high and easily obtained by men. Most women in rural Zanzibar do not own houses. They do not become electricity customers nor owners of appliances. Yet, they contribute substantially to financing the family’s high cost of electricity. This constitutes a problem the day their husbands want a divorce, when they are left with extremely little material wealth. Electricity may in this way have made women even more dependent on men than before.

In everyday life, there is also a concern among some people that electricity’s high costs may negatively affect the family’s food security. Perhaps the reduction in cooked meals implies that people eat less than before? (this has not been investigated from a detailed, nutritional point of view). At the same time, the alternative, to buy expensive kerosene for lighting and batteries for the radio, is also a financially risky business. In 1991, it would take a family 9 years to pay back their investment in electricity for light and radio as compared to the use of kerosene and batteries. (Thus after 9 years it would become cheaper to use electricity than the alternative fuels). In 2005, due to a rise in the kerosene price, the pay back time had been reduced to 4 years.

Information Project: People from Uroa (working for the Information Project) explaining the use and dangers of electricity during a public meeting in Uzi Village, 2005.

It seems that people sleep less than before. Those without electricity at home sometimes complain that their neighbours are tired after having watched television until midnight and therefore quarrel more than before. Many parents are concerned that children, especially boys who are freer to stay out late at night, are too tired to learn properly at school.

But in the larger picture, such effects are considered as details. The coming of tourists, however, is seen as a greater challenge. The foreigners are often considered to have an improper conduct that could affect new generations in unfortunate ways (alcohol, drugs, clothing etc). If tourism provided people with jobs, this would have balanced the picture, but so far, rural Zanzibaris mostly experience the negative side of this growing business. Still, people are strikingly warm and welcoming towards foreigners. Knowing the social and moral cost of the tourists’ presence in the neighbourhood, this attitude surprised me again and again.

What are the implications of your findings?

I hope to have demonstrated that asking and realising the question of “how” is just as important as “what” (e.g., electricity). My main case, electrification in Uroa village, was atypical in the sense that they were not included in project plans but ended up with the highest number of electricity customers and the only village in Zanzibar with street lights.

I try to show that the success of Uroa was not random, but a direct result of their own initiative and contribution in the process, including the use of magic remedies. People in the village are very proud of what they achieved. They demonstrated in practice what participation is about. Such involvement is possible despite the “heavy” and apparently predetermined nature of infrastructure projects.

On another level, the study revealed that ordinary customers have not been properly informed about how the accounting system works. As a result, the think they are being cheated by the utility and their own morality regarding illegal use becomes affected.

In response to these findings, Norad (The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation) agreed to finance an information project in Zanzibar where we put emphasis on electricity’s possibilities but also difficulties. Two teams (both genders, people from town and people from villages experienced with electricity) travelled around the islands for two months and held fabulous speeches:

– Do you think the ocean is dangerous? (Yes)

– We still go out fishing, don’t we? (Yes)

– It is the same with electricity. You just have to know how to deal with the danger…

I have received feedback from management in the World Bank’s evaluation group that the study is interesting also from their point of view. If the experiences from Uroa can be useful to people working and living elsewhere, nothing would be better.

In anthropology, I think there is a need for more studies on electricity and energy. Economists and engineers have had a claim to this field for a long time and there is renewed focus on energy these days.

This was exciting to study, I suppose? You’ve been there during the first years with electricity?

Yes, I arrived in Uroa village in 1991, one year after village electrification. When I came back for the main fieldwork in 2000, they had 10 years of experience with the new technology; more appliances, more households connected. I had expected to find many women cooking food with electricity (what people in 1991 said they expected would be the case). But very few did.

I thus learned the old lesson that people do not necessarily do what they say they want to do. There are many reasons why, but it is interesting to try to understand such discrepancies. I have also returned to Zanzibar in later years as a consultant. People’s use of electricity, as any practices, change in a fascinatingly rapid manner.

What was it like turning the doctoral dissertation into a book? A long process?

It took about one year to get the process started and then 1 1/2 years in production, so yes, it was a long process. Berghahn’s external reader had some very useful comments on an overall level that I have tried to respond to. Otherwise, I felt quite on my own in the process – the luxury of having a splendid supervisor (Aud Talle in my case), was gone. But when writing the thesis I had kept in mind Unni Wikan’s advice to think about the thesis as a book. To a great extent, I could keep to the same structure.

Why did you translate the book into Swahili?

The idea was initiated by one of my friends in Uroa during fieldwork. He does not speak or read English. He told me enthusiastically that he was thrilled about the thought of knowing that other people in East Africa would read the story from Uroa – and learn about electrification. Thus he was concerned about sharing the material with other groups.

I was just as concerned about making this man (and his co-villagers) have access to their own story. The Norwegian Embassy later kindly agreed to finance the translation of a shorter version of the material and have a book produced in 500 copies. This would perhaps not have been the case had I chosen another, less ‘relevant’ topic in their eyes.

But I think it would be a good thing if phd-budgets in general included the important step of making results accessible to the people under study. The book was recently distributed to 35 households in Uroa and schools across Zanzibar.

By the way, I remember Pat Caplan, the main opponent during the defence of the thesis, asking me what reactions I would expect from people in Uroa if they had access to the written material. I said that they would be likely to be proud and agree with most parts, but also surprised and perhaps even disturbed regarding other parts. In particular, the critical analysis of women’s position and the social exclusion of people in opposition to the government, could produce some reactions. I did not leave these aspects out in the published book, which is entitled Umeme: Faida na Athari Zake. Uzoefu Kutoka Kijiji cha Uroa. (Electricity: Its benefits and challenges. Experiences from Uroa Village). So far, I have not heard any reactions from the village, but of course, I am quite exited.

What are doing right now?

I am with the Centre for Development and the Environment (SUM) at the University of Oslo, who have hosted me since I first came in 1999 as an engineer wanting to learn and do anthropology. As member and secretary for a reference group of a trust fund in the World Bank (TFESSD), I discover that the Bank has come quite far in analytical work that integrate work on social development, gender and infrastructure.

The link between gender equality and energy continue to be one of my main interests, and I also currently work on a little piece called Why do poor people steal electricity?

Electricity is a social phenomenon, and I hope that many anthropologists will join this fascinating field. I think we are both needed and appreciated.

Thanks for the interview!

>> information about the book by the publisher (Berghahn Books)

>> more information about Tanja Winther

Related texts online by Tanja Winther:

Tanja Winther: Empowering women through electrification: Experiences from rural Zanzibar (pdf)

Tanja Winther: Social Impact Evaluation Study of the Rural Electrification Project in Zanzibar, Phase IV (2003-2006) (pdf)

Tanja Winther: Information Project. Zanzibar Rural Electrification Project, Phase IV. Project Report (pdf)

For readers in Norway: Her book will be presented in Klubben, University Library, Blindern, University of Oslo, Tuesday 9.12. from 16-17 o’clock.

Links updated 1.6.2021