“They’re natural born killers. They’re good, they’re lethal, they’re fantastic. I love working with them”, says Major Robert Holbert. He was part of the first Human Terrain Team in Afghanistan in 2007 and tells his story in a fascinating interview with Lisa Wynn at Culture Matters.

The interview gives insight in the way HTS-people (“cultural advisors” for the US-army) think. And it uncovers that their way of thinking only works within their own cosmology – only as long as you accept that it is okay to colonize / occupy Afghanistan or Iraq:

Lisa Wynn: OK, well let me ask a hard question, the kind of question I can imagine opponents of HTS posing. Yes, you’re saying this saves lives, and probably that’s true. But at the same time, it facilitates a military occupation of another country. You say it’s about winning a war. But talking about winning, it takes the war for granted. In the end, you’re facilitating the U.S. occupation of another country. How would you answer that?

Robert Holbert: [sighs] I’m not going to completely disagree, it’s not… God. It is what it is. OK, you say we’re an occupying army, we’re an occupying army. If that’s how you look at it, that’s how it is. What else do you call it when you’re not from the country and you’re in it? But if you’re going to fight it, then you’re there. This is an opportunity to change the culture of the military, this is our golden hour as progressives, and yeah, we’re in a country, we’re occupying it, but I’m trying to work myself out of a job, you know.

>> continue reading at Culture Matters

It reminds me of what Kerim Friedman wrote three month ago in his post The Myth of Cultural Miscommunication (Savage Minds, 26.6.08):

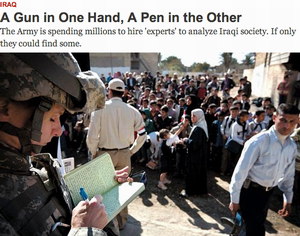

Treating the military’s lack of respect for local cultural knowledge as a cultural problem which can be solved by hiring anthropologists ignores the very real ways in which the military itself operates as a system for producing knowledge about the world, and the role of local knowledge in that system.

I haven’t written about military stuff recently, so in case you’ve missed some earlier posts on this issue in the anthrosphere, you might be interested in reading that The Human Terrain System spreads to Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean (Open Anthropology, 7.9.08) , about resistance against Pentagon’s Minerva project (military-social science partnership) (Culture Matters 5.8.08) and a review of an article by embedded journalist Steve Featherstone about the HTS entitled “Human Quicksand” (Culture Matters 29.8.08). Culture Matters provides also an annotated bibliography on HTS, Minerva, and PRISP

SEE ALSO:

Cooperation between the Pentagon and anthropologists a fiasco?

Anthropology and CIA: “We need more awareness of the political nature and uses of our work”

"They’re natural born killers. They’re good, they’re lethal, they’re fantastic. I love working with them", says Major Robert Holbert. He was part of the first Human Terrain Team in Afghanistan in 2007 and tells his story in a fascinating interview…