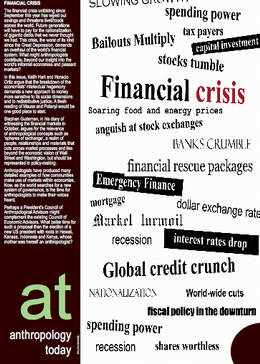

Anthropologists have largely left the global effects of economic globalisation to economists. Now in this worldwide financial crisis it is the time for anthropologists to renew an engagement with political economy, Keith Hart and Horacio Ortiz write in their guest editorial in the new issue of Anthropology Today:

Anthropology’s relevance to the world would be enhanced if some of us adopted a more self-conscious strategy of seeking to understand the present crisis and its consequences for society at all levels.

(…)

We should try to bring the distributive consequences of finance down to a concrete level. Readers might then be able to engage with money not as a superhuman force with devastating effects, but as the outcome of ideas and institutions that can and should be changed by human action.

(…)

The breakdown of the economists’ intellectual hegemony represents a chance for us to link our engagement with people’s lives to anthropology’s original mission to understand humanity as a whole.

There are many ways to do this:

One method of doing so would be to analyse the everyday practices of professionals in financial corporations, states and regulatory bodies (Ortiz 2008), but also those of the people who entrust their monetary resources to them or are barred from access to the process.

(…)

Kula objects have magical power for those who exchange them, but anthropologists have shown their social logic and instrumentality. We have always invented concepts to describe and explain social processes quite different from those familiar at home. The current crisis presents us with a compelling reason to do so again, this time in a global context.

Anthropologists can do no better than to renew their engagement with the writings of Marcel Mauss and Karl Polanyi. Their perspectives on political economy can help us to make sense of the current situation and to recommend alternative paths forward according to Hart and Ortiz.

In his famous work “The Gift”, Mauss observed,

…that in contemporary capitalism the wealthy classes acted increasingly as if they did not belong to a social order that made redistributive obligation a condition of their hierarchical privilege. Their amnesia when it came to the ‘gift’ was not just a function of power, but of an accumulation of power that considered itself to be socially unbounded. As a result, heightened strife put the social order itself at risk.

Polanyi showed in his famous work The great transformation (1944) how markets became disembedded from the rest of society. Like Mauss, Polanyi was concerned with the ideas that defined money, the rules of its use and the social distinctions that made its circulation possible and legitimate:

He too contended that the classes who benefited from markets, particularly high finance in the decades before the First World War, neglected the interests of the rest of the population, with devastating consequences for society. (…) He identified the historical dialectic or ‘double movement’ whereby the drive of capitalists to escape from social constraints met the countervailing power of classes and institutions (such as those adhering to the welfare state) acting in society’s self-defence. (…) The distribution of resources, according to him, should not be left to the search for profit in market relations, but needed also to acknowledge solidarity between all members of society.

(…)

Anthropologists following him would thus explore how the social struggles over money are understood by the participants, and with what consequences for distribu- tion itself. This would offer a critique of the pretence that economics is not social or political; beyond that, it would constitute a research programme.

Polanyi and Mauss made sure that their more abstract understandings of political economy were grounded in the everyday lives of concrete people:

An unblinking focus on distribution at every level from the global to the local reveals how the social consequences of political economy and the way it is understood by those who make it are one and the same social process. The current crisis renders this insight particularly visible, since it challenges contemporary financial ideas, while its tangible distributive effects are felt and feared throughout the world.

It is no coincidence that economic anthropology was last a powerful force in the 1970s, when the world economy was plunged into depression by the energy crisis, Hart and Ortiz write:

Now, if ever, is the time for anthropologists to renew an engagement with political economy that went into abeyance then. The prize at stake for our discipline as a whole is much larger than the revival of one of its parts.

Anthropology’s highest mission is to start from where people are and go with them wherever they take you. That means engaging with their visions of the world, perhaps to catch a glimpse of the world humanity is making together. What better time to follow this imperative than when the model the world has been compelled to live by for three decades is in such disarray?

The editorial is not accessible for readers outside the university world, but Keith Hart has published a different version of the editorial on his website (and many related papers as well)

SEE ALSO:

Used anthropology to predict the financial crisis

Anthropologist: Investors need to understand the tribal nature of banking culture

What anthropologists can do about the decline in world food supply

The last days of cheap oil and what anthropologists can do about it

After the Tsunami: Maybe we’re not all just walking replicas of Homo Economicus

Why were they doing this work just to give it away for free? Thesis on Ubuntu Linux hackers

Anthropologists have largely left the global effects of economic globalisation to economists. Now in this worldwide financial crisis it is the time for anthropologists to renew an engagement with political economy, Keith Hart and Horacio Ortiz write in their…